The Polyvagal Theory describes the autonomic nervous system consisting of three main pathways: dorsal vagal, ventral vagal and sympathetic. The dorsal vagal and ventral vagal are part of the parasympathetic branch of the nervous system, often known simply as ‘rest and digest’. The sympathetic branch is often known as our ‘fight or flight’ response. According to Steven Porges the founder of the Polyvagal Theory, the vagus nerve is not a single nerve but a “family of neural pathways” and has a major role in the parasympathetic branch of the nervous system.

The Polyvagal Theory highlights the evolutionary continuum in the autonomic nervous system from dorsal vagal, to sympathetic, to ventral vagal (see diagram below). The dorsal vagal is known as the immobilization system or the system that responds to life threat, it is the most primitive system seen in invertebrates and mammals who ‘feign death’. The sympathetic system is known as mobilisation system with fight or flight response, and also freeze, which is typically a hybrid state of sympathetic and dorsal vagal. The ventral vagal system is known as our social engagement system, where we connect and feel safe.

However, humans are highly complex beings, who are still evolving in the capacity for social engagement without fear or threat. The Polyvagal Theory describes also a spectrum of mutual hybrid states which are navigated moment to moment in waves or spirals of movement in our daily life. An individual nervous system will often prefer certain core states, and orient from a core or favoured self state. This core self state coupled with other preferred self states then shapes how the autonomic nervous system responds in different life settings of safety, danger, life threat. The diagram below shows a depiction of some examples of the hybridity states we can inhabit in our being, as well as the commonly known pure states of flight, fight (sympathetic), shutdown (dorsal vagal), and connect (ventral vagal - social engagement).

In the diagram above, the state of appease for example in yellow at the top is a combination of sympathetic activation alongside social engagement, it has a sympathetic mobilised charge to it. The state of dorsal appease bottom right in crimson is a combination of dorsal and ventral vagal, where there can be intense collapse, withdrawal or shutdown whilst simultaneously present with some social engagement. The charge here is often felt as slow, heavy, engulfing and despairing. This has quite a different feeling tone, from the state of deep intimate contact which involves the dorsal and ventral vagal and requires immobilisation without fear. Another example is play: play that is fun and non-competitive requires high social engagement as well as some sympathetic stimulation. There are various ways we play, we can play just with words and laughter, or we can play with movement in dance, or play with a puppy. All of these various types of play will engage the sympathetic system and ventral vagal systems to varying degrees. In children play may be harmonious for a while and then quickly leads to competition and conflict, here the ventral vagal aspect is challenged by increasing arousal of sympathetic system. Similarly in our adult relationships this change from social engagement to sympathetic arousal can happen were we enter into fight or flight states quite quickly. The hybridity and complexity of the states are vast and this diagram just gives an example of some of the possible hybrid states, there are many more.

The Polyvagal Theory and Trauma

The Polyvagal Theory helps to explain why the body is of primary importance in healing trauma. The Somatic Experiencing work of Peter Levine and his early book “Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma”, as well as the work of Bessel Van der Kolk and his well known book “The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma” , both highlight clearly the importance of the Polyvagal Theory. There are many other experts and academics in the psychotherapeutic field working with trauma and the body, such as: Pat Ogden (Sensorimotor Psychotherapy), Alan Schore (Psychologist and researcher in field of neuropsychology and right-brain Psychotherapy), Stanislav Grof (LSD and psychotropic breath work research in relation to birth experiences, deep emotional states and altered states of consciousness), to name just a few. Their research and psychotherapeutic practice in the field of early developmental trauma and traumatic experiences is elucidating the importance of the Polyvagal Theory for understanding how we need to change the way we treat mental illness, and the way we structure and inhabit material environments and social systems.

“Since noisy environments that contain low-frequency sounds are triggers of predator to our nervous system, removing low-frequency sounds and background noise will optimise the healing potential of the clinical space. It is important for the clinical space to be relatively quiet. Many clients with a trauma history are extremely uncomfortable in public places.... If we know this, why don’t we create environments where they will feel safer?”

NATURE AS AN ANTIDOTE TO TRAUMA

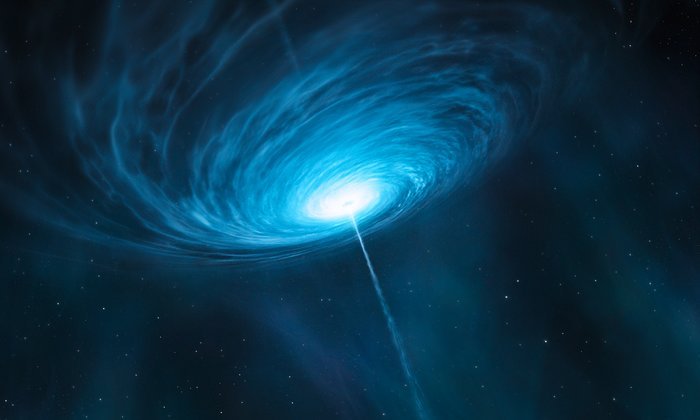

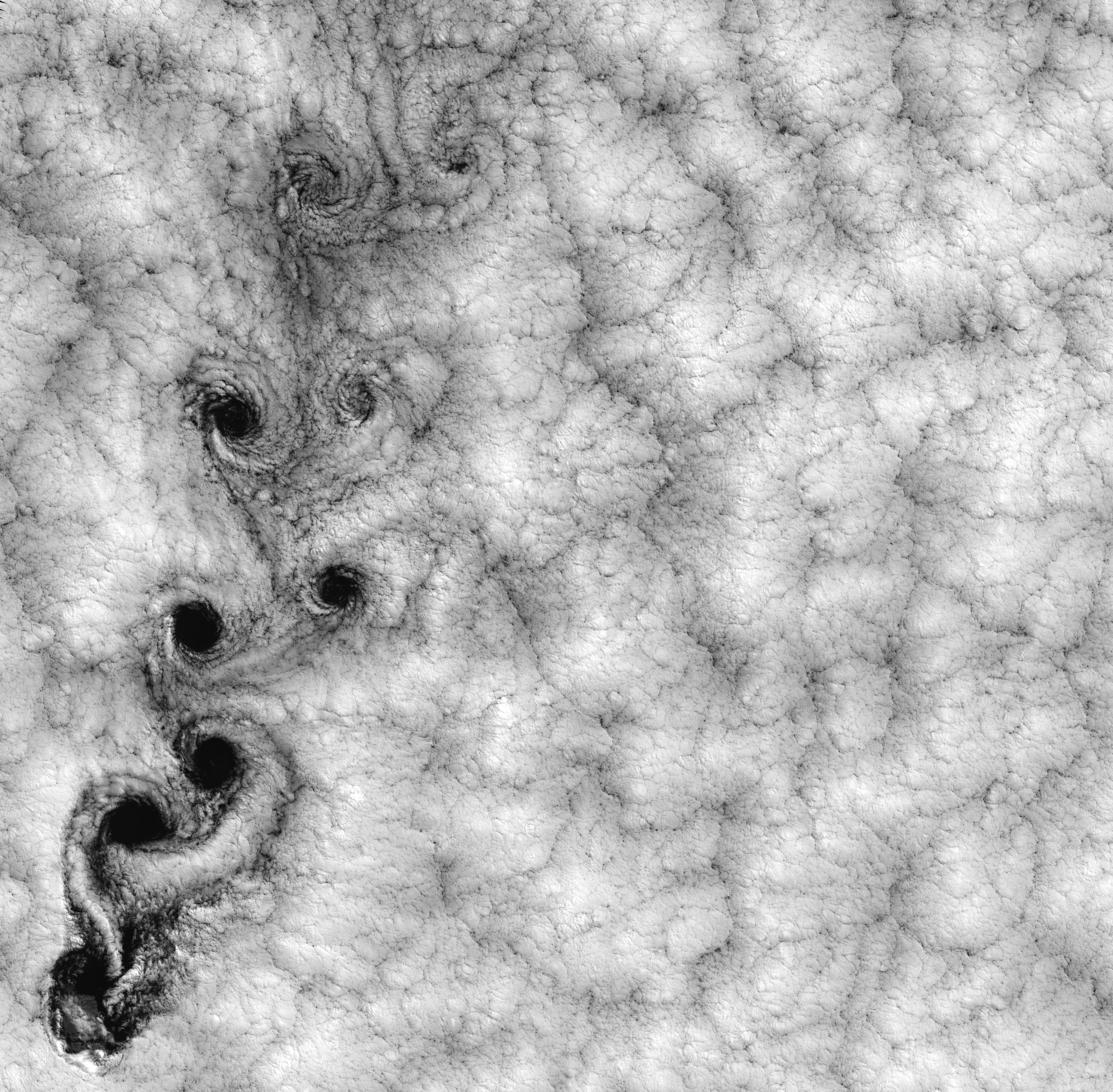

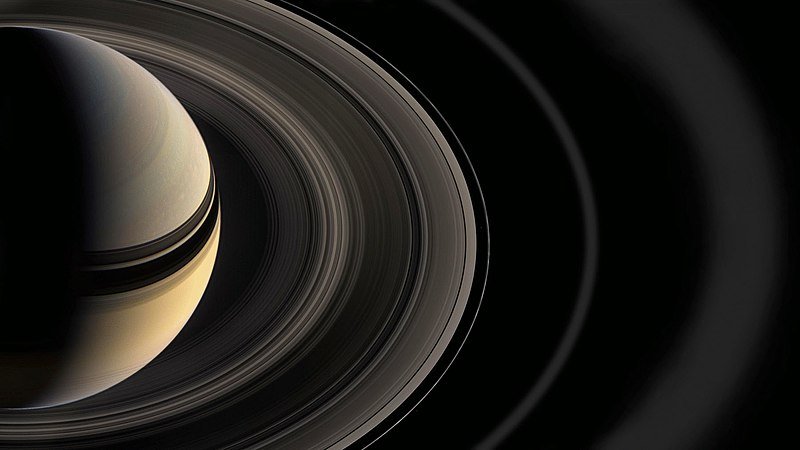

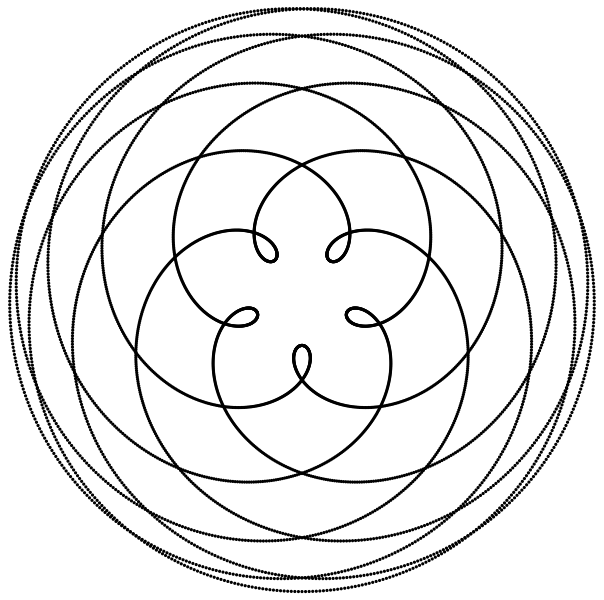

As well as various theurapeutic modalities that work with the body and are highly important for developing the social engagement system, nature is often experienced as an antidote to trauma. When we allow ourselves time to deeply connect with nature and savour the experience we enter into a restore state with feelings of contentment and ease. Listening to the sounds of nature, observing the fractals in nature are two simple mindfulness exercises which have been shown in scientific research to have a regulating effect on the autonomic nervous system, helping to reduce stress levels. Below is a slideshow of images showing the various fractal patterns observed in nature. Fractals are shapes which have simple repeating patterns that create infinite complexity and dynamism. They are evident in nature and the universe, from the humble romanesco brocolli, to lofty clouds, to the magnificent peacock plumage, and to the rings of planet saturn out in the cosmos. The movement of Venus around the Sun, viewed from earth, is also a beautiful fractal pattern, known as the Rose of Venus or the Pentagram of Venus, and seen in many flowers from sunflowers to roses, to datura.

Listening to the song of Tūī

I invite you to take a moment to create some quiet space, let yourself observe your body, and listen to this audio below of a Tūī’s song. What do you notice when you invite this sound into your body, what does it evoke in you?

I wonder… perhaps one day these kinds of simple mindful exercises may become part of our system of medicine, and part of physical spaces in hospitals. Much like beautiful gardens and sacred places on earth can be elixirs for the wounded soul.

References

Stephen Porges. The Pocket Guide to The Polyvagal Theory : The Transformative Power of Feeling Safe, 2017.

Deb Dana. Polyvagal Exercises for Safety and Connection, 2020.